A Brief History of Ready to Wear is a 4-part feature exploring the events that led from made-to-order fashion, through the ready to wear revolution, and up to the present problem of fast fashion.

Fashion is an international market of art, an exchange of inspiration, ideas, and industry.

While humans have always adorned ourselves in an act of self-expression, we have not always bought off the rack or shopped online. Fashion wasn’t always fast. In order to understand all of the complexities of the fashion world today, and the greater forces that shape our manner and means of consumption, it is important to understand how our garments come to life.

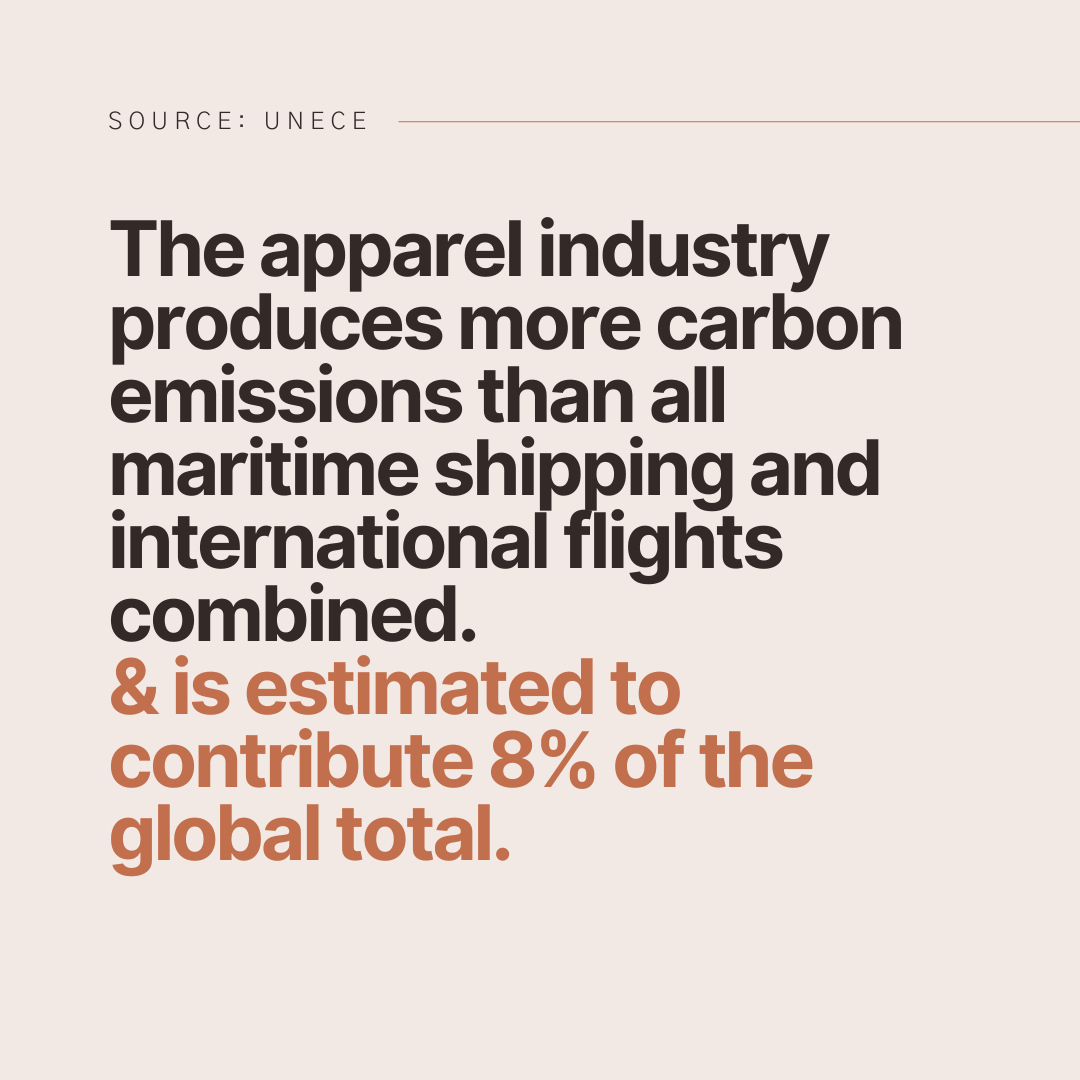

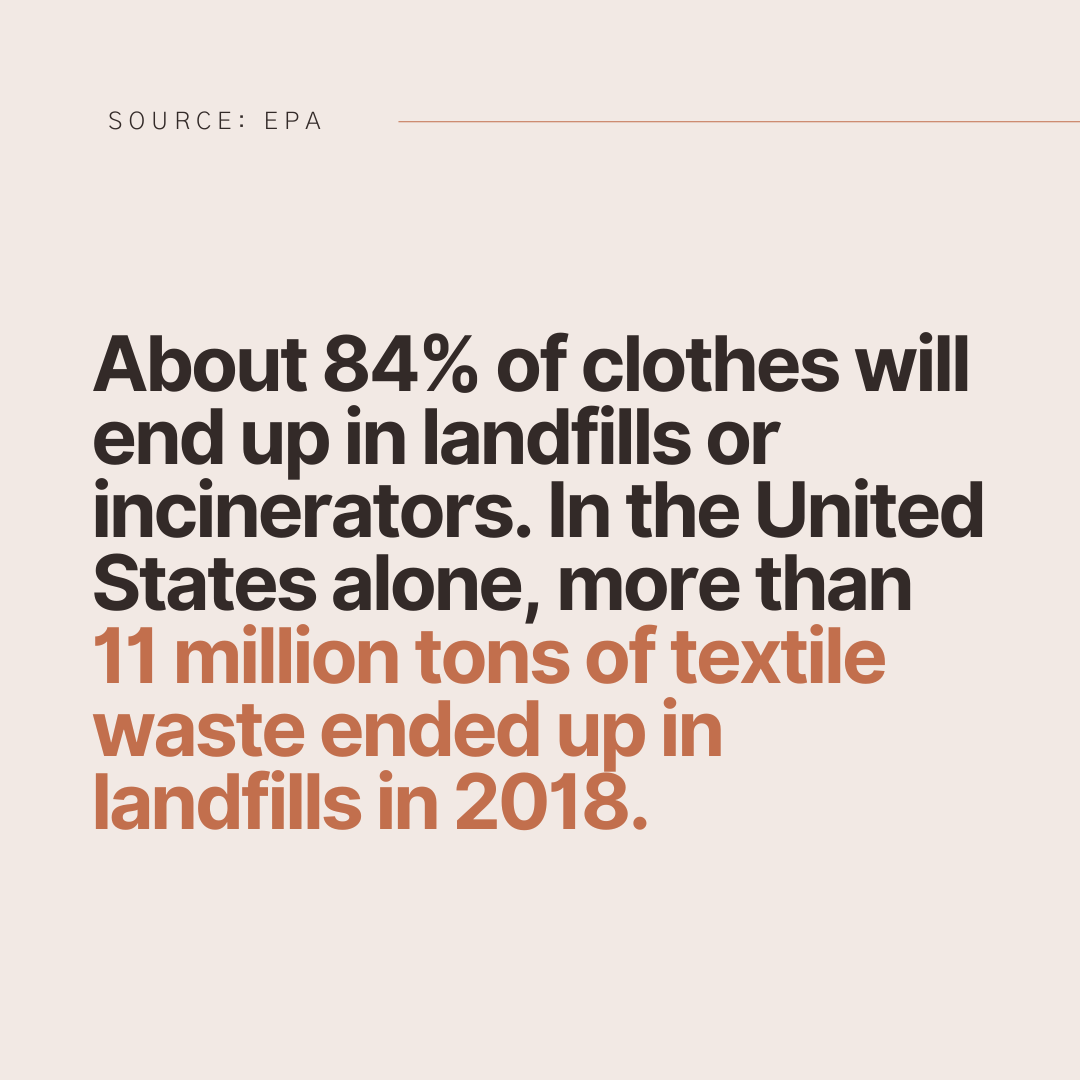

For the final chapter of this installment, we arrive at fast fashion, a phrase that aims to encapsulate the many complex and systemic issues of an accelerated and unsustainable industry.

What is Fast Fashion?

Fast Fashion commonly refers to low-priced clothing that is quickly produced to follow trends and is released continuously, rather than in seasonal collections. Fast fashion is used as a name for the systematically unsustainable practices we see in the modern production of ready to wear apparel.

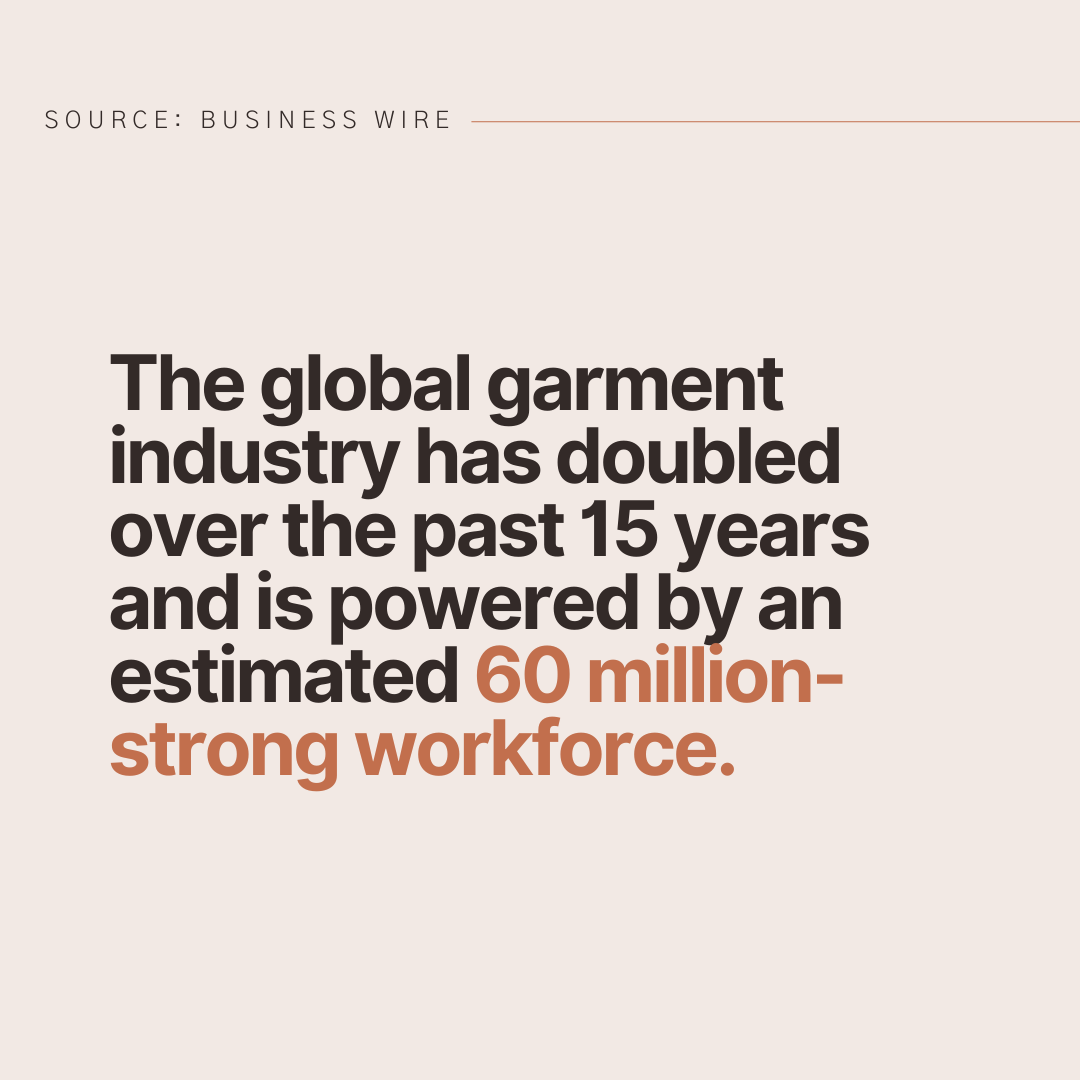

Ready to wear garments began as affordable and accessible alternatives to individually ordered or homemade garments. As we explored in the history of production, shopping, and sizing, fashion has left its roots in function and fit to become, in many ways, a commodity. The culture of clothing and consumption habits have changed as a direct result of decades of industry efforts to maximize profits.

In 2021, 400% more clothes were produced

than in 2001.

How did this happen?

Staying informed on policy changes and developments in industry standards is a key part of our sustainability mission.

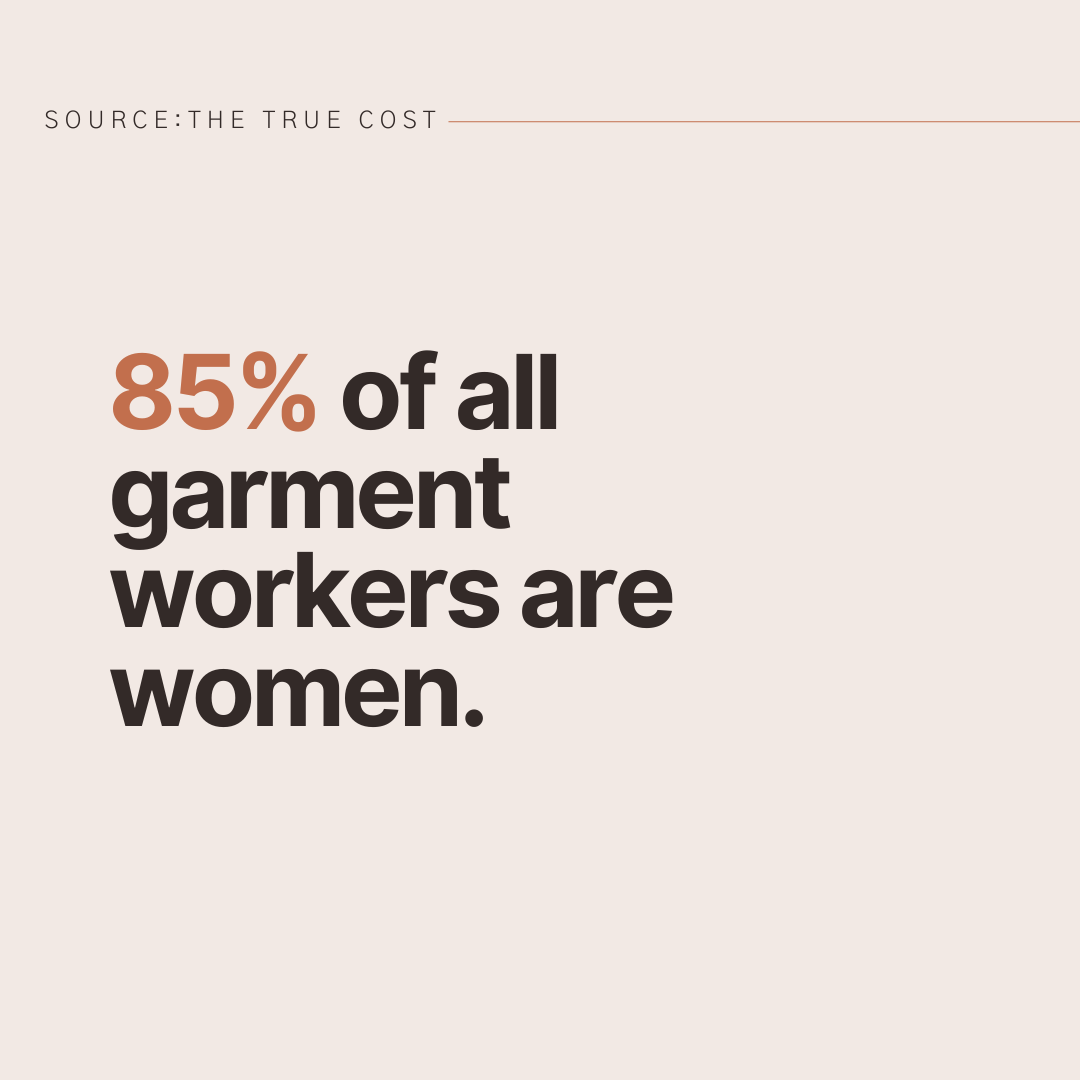

Fast fashion is enabled by unethical and exploitative practices, to both the material resources it uses and the people it employs. While this didn’t happen overnight, it did happen fast.

Government policy regulates industries, and throughout the 1990’s there were consecutive changes to international trade regulations in the United States. The release of the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) sealed the deal with the removal of most import restrictions and duties on foreign-made clothing. By manufacturing abroad, U.S. businesses were able to utilize the under-regulated labor practices available for a fraction of the cost.

Due to American corporations transitioning to international outsourcing between 1990 and 2011, the U.S. garment industry suffered a loss of 750,000 jobs, a decline of over 80% as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

A common misconception is that lower international wages are simply relative to their local economies, as the US dollar has more purchasing power than many other currencies. However, many garment workers are underpaid by the economic standards and poverty rates in their own nations. For example, the Asian Floor Wage Alliance stated that the living wage, or the wage needed to survive in India, is 29,323 Rupees a month. Indian garment workers are salaried at less than half of that, making only 10,000 to 12,000 Rupees a month, ($133 to $160USD).

Neva Nahtigal from the international office of The Clean Clothes Campaign attested that “The global economic model that drives down prices and pits low wage country against low wage country is too strong. It’s a fact that the workers who make almost all the clothes we buy live in poverty.”

She’s right, fast fashion is a human rights issue. The labor practices are as unsustainable as the tangible resources that fast fashion exploits. Many experts argue that in order to tackle the fast fashion problem, we should start by addressing its labor practices. UC Santa Barbara Environmental Scientist Roland Geyer published the claim that “labor, rather than green products or materials, holds the key to social and environmental sustainability,” in his book The Business of Less: The Role of Companies and Businesses on a Planet in Peril.

There’s a reason fair labor is embedded in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. By starting with fair wages and greater protections for garment workers, the industry will be forced to adapt. Fair wages and rights for workers would correct unsustainable production speeds, by ending forced overtime and 12+ hour workdays. Safer working conditions would also force regulations on hazardous chemicals that harm both workers and the environment.

Where do we go from here?

It might seem contrarian, but we go slow!

Slow fashion is a counter movement in the apparel industry that stands for a return to tradition through conscious design and informed choices. Thoughtful and intentional design considers each element of the supply chain, from the source of initial materials to the conditions of its garment workers. Slow fashion is a broad term used to capture a rejection of fast fashion principles.

What does slow fashion look like for designers and brands?

Slow fashion can be interpreted differently by every business and creative, but is supported by sustainable choices that align best with your own practices. Designing with greater intention creates products that last longer, are crafted from better materials, and are able to be repaired. Some brands are piloting repair services and resell programs to support the longevity and quality of their final products.

For our clients and our team at Rule DD, slow fashion means local production in small batches, made with carefully selected materials. All our work is designed, developed, and produced here in California, and we strive to nourish and grow the local garment industry.

Author of The Conscious Closet, Elizabeth Cline reminds us that “the most sustainable thing you can do is try to buy something you know you’re going to wear.”