Slow fashion is both an homage to a tradition as well as a living practice of production.

We often mention the community and network of relationships we have here in Los Angeles

& the locality of the Garment District is what makes that possible.

Being able to create, collaborate, and manufacture in a central space provides the connectivity necessary for our industry to thrive. With the 2040 Community Development Plan putting our district at risk, it's important to know the history of our labor and industry.

The Beginnings of the Garment District.

While more commonly called the Fashion District now, for most of its life it was known as the Garment District.

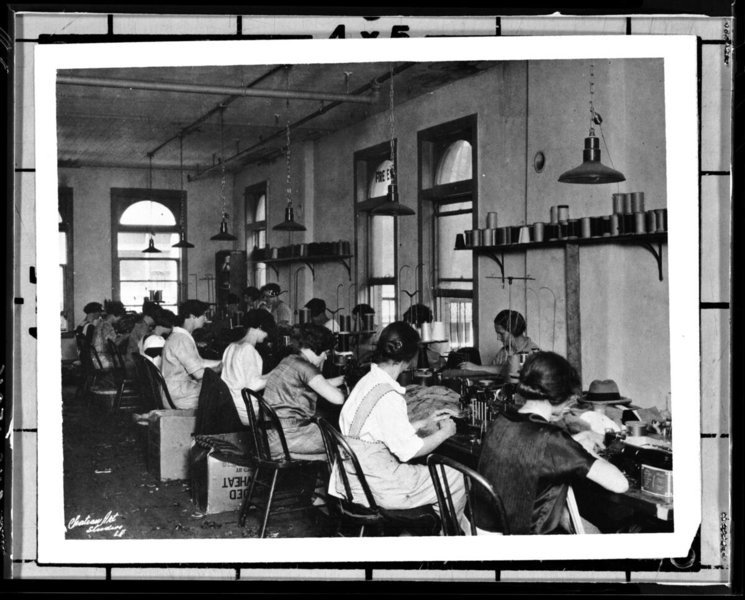

Female workers assembling shirts at a Garment District factory in Los Angeles, 1940-1950.

Garment production began in Los Angeles in 1890 with the manufacturing of men’s overalls by Morris Cohn & Company, later named Cohn, Goldwater & Co. The founder, Morris Cohn, was only 21 years old at the time, and is rumored to have brought the first powered sewing machine to the West Coast.

The business continued to expand, and in 1899, their production specialized in workwear like workmen’s overalls and trousers, but also included dress shirts and daywear. Though this was the first manufacturer in LA, it represented the demand and later development of a larger district and network of businesses.

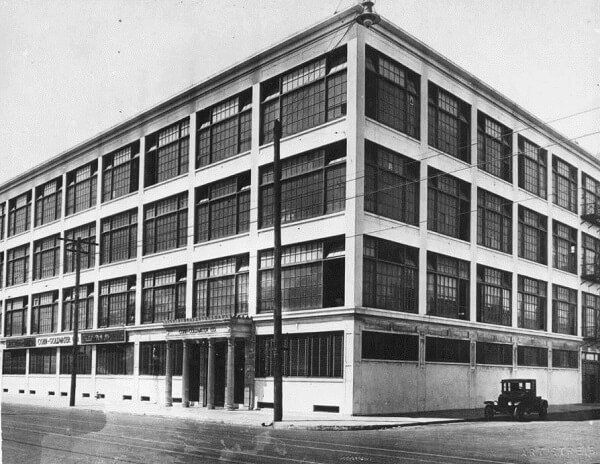

In 1909, the company moved to the first modern steel-reinforced concrete factory building in Los Angeles, at 12th and San Julian Streets, now 525 East 12th Street. What was once their factory floor of 50 factory workers, became a LA Cultural Historical Monument.

The Garment District truly came into its own in 1921 with the founding of The Associated Apparel Manufacturers of Los Angeles. This coalition was organized by apparel manufacturers and their collaborators and reached 130 members in the early years that followed.

The Cooper Building on Ninth Street also began its construction in the 1920s. The Cooper Building marks the beginning of collaboration and interconnection between design, development, and production, as it quickly became surrounded by men’s and women’s showrooms. By 1937, Southern California was home to 250 buyers from the nation's largest department stores, and was considered the sportswear capital of the country.

As the silver screen turned to color, Los Angeles continued to grow as a fashion epicenter with the pull of glamour and media.

California was popular for swim and sportswear as well as the costumes and garments for Hollywood starlets. This diversified the district from its roots in workwear and attracted a new wave of entrepreneurs and garment workers.

The low start costs for entering the industry influenced the growing interest too. In the 1970’s, it was said that the network of the district allowed for quick turn around. With a type of buyer called a factor, under financed manufacturers would be paid for their garments as soon as they were shipped, rather than having to wait for retailers to pay. Some alleged that a husband and wife duo could start their own manufacturing operation with only each other and $10,000.

“The area is largely unknown to most Los Angeles Residents, and before they know it, it may be gone. Industry observers say that the unique close-knit cluster of factories may be moving on to other parts of the city and country. For now, it is the most exciting, painful, funny, tragic, cruel, and tempting business district on the West Coast.”

- LA Times, February 2, 1972

While the labor of the garment district has always been present, the property value and appeal haven’t been. A 1972 an article in the Los Angeles Times titled “A Ravaged Street of Wear” stated that the district spanned from 3rd to 11th Street and was an estimated 2,000 workers strong, a number that now seems minuscule when compared to the 2023 Garment District workforce of 20,000.

Though it was then described as ravaged due to the crowded, noisy streets, pollution, and neglected buildings, the residents and workers themselves spoke proudly and highly of their district. One garment worker said “Here, we have a closely knit group,” and when asked about the differences of NYC and LA, “We socialize, see each other at lunch, with many there is a friendly atmosphere- congenial.”

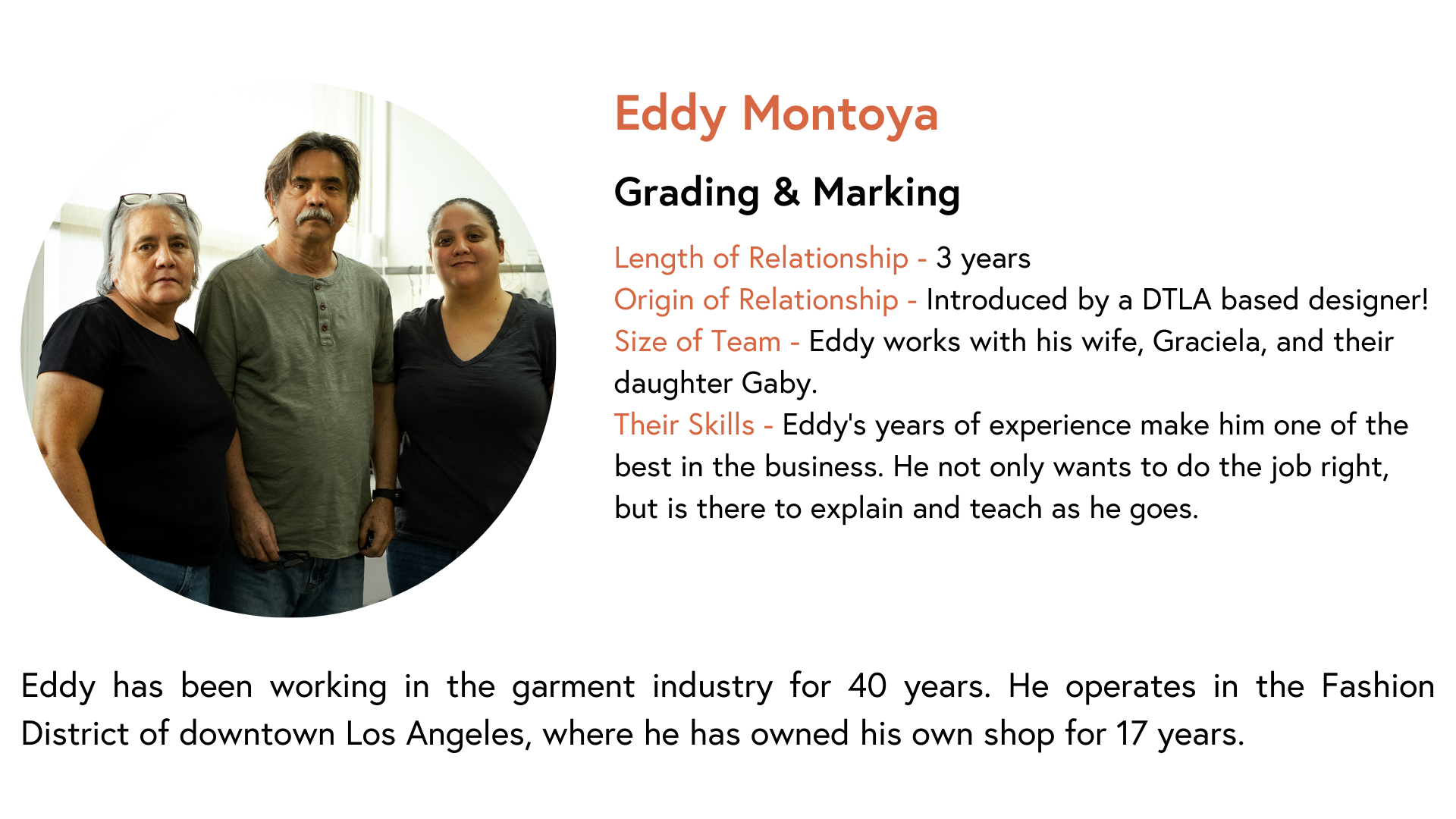

The Fashion District today is home to thousands of skilled workers, with 21 years average experience. Many of these workers have learned their skills through family businesses, and are inspired to continue these legacies and the generational knowledge of their crafts.

Why does the preservation of the garment district matter?

The history of camaraderie and community has always existed for our district, and we aim to keep that alive. It wasn’t until 1996 that the district was rebranded from Garment to Fashion in an attempt to improve the area and surrounding blocks. This was initiated by the first property based business improvement (BID) in LA. Called the LA Fashion District Business Improvement District (BID), it is a private non-profit corporation created and maintained by property owners.

Though almost 30 years ago now, that rebranding of the district represents a greater conversation. The Garment District is still standing because of its industrious roots and intertwined community of laborers.

“The Garment District is not a relic from a past industry, it is a living history of California Made production and generational labor.”

”

The work of this industry and unique qualities it holds, are only possible through our localized community of collaboration.

Existing in community with our partners allows us to strengthen our communication and camaraderie through a shared space. There is value in holding space together, and sharing a presence in the community.

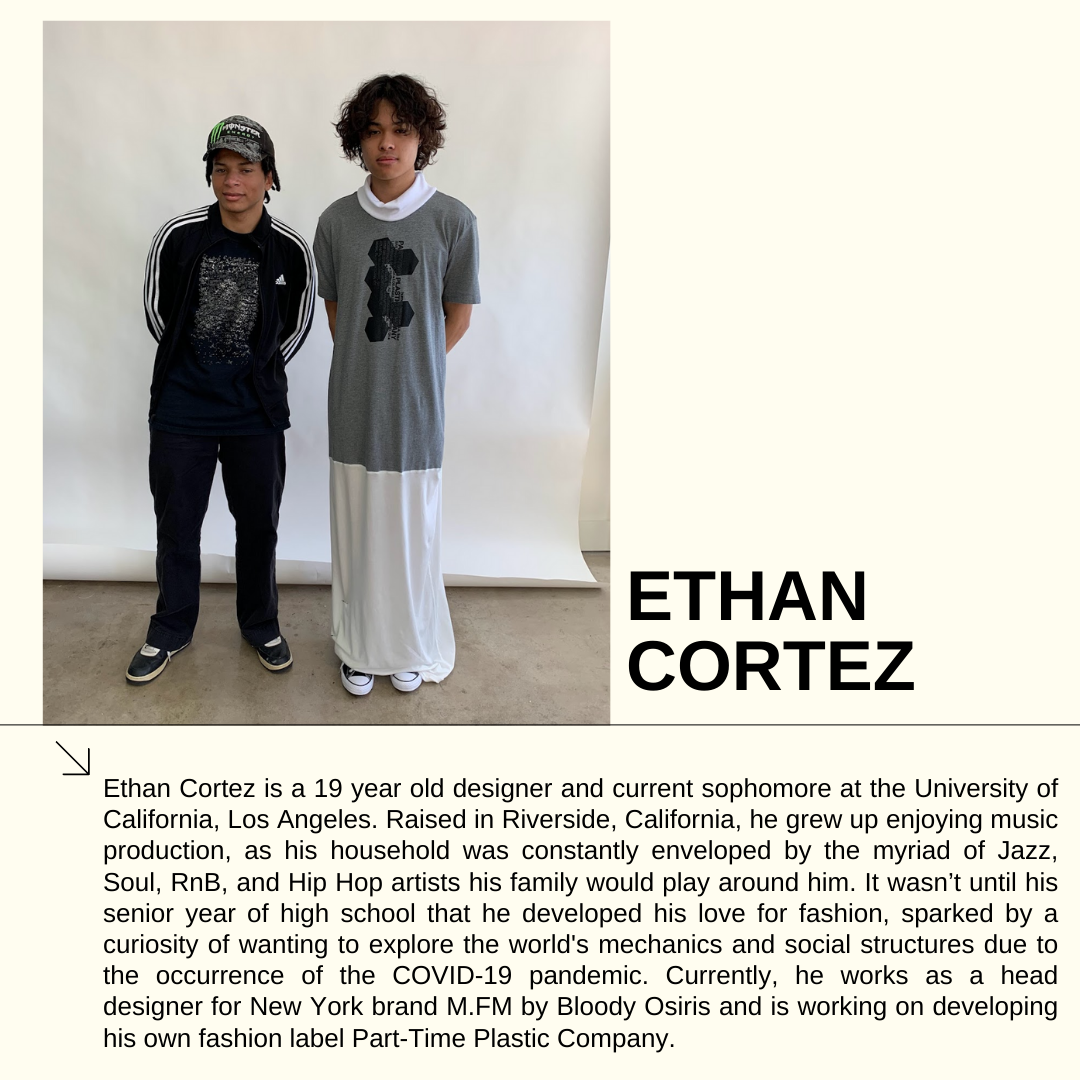

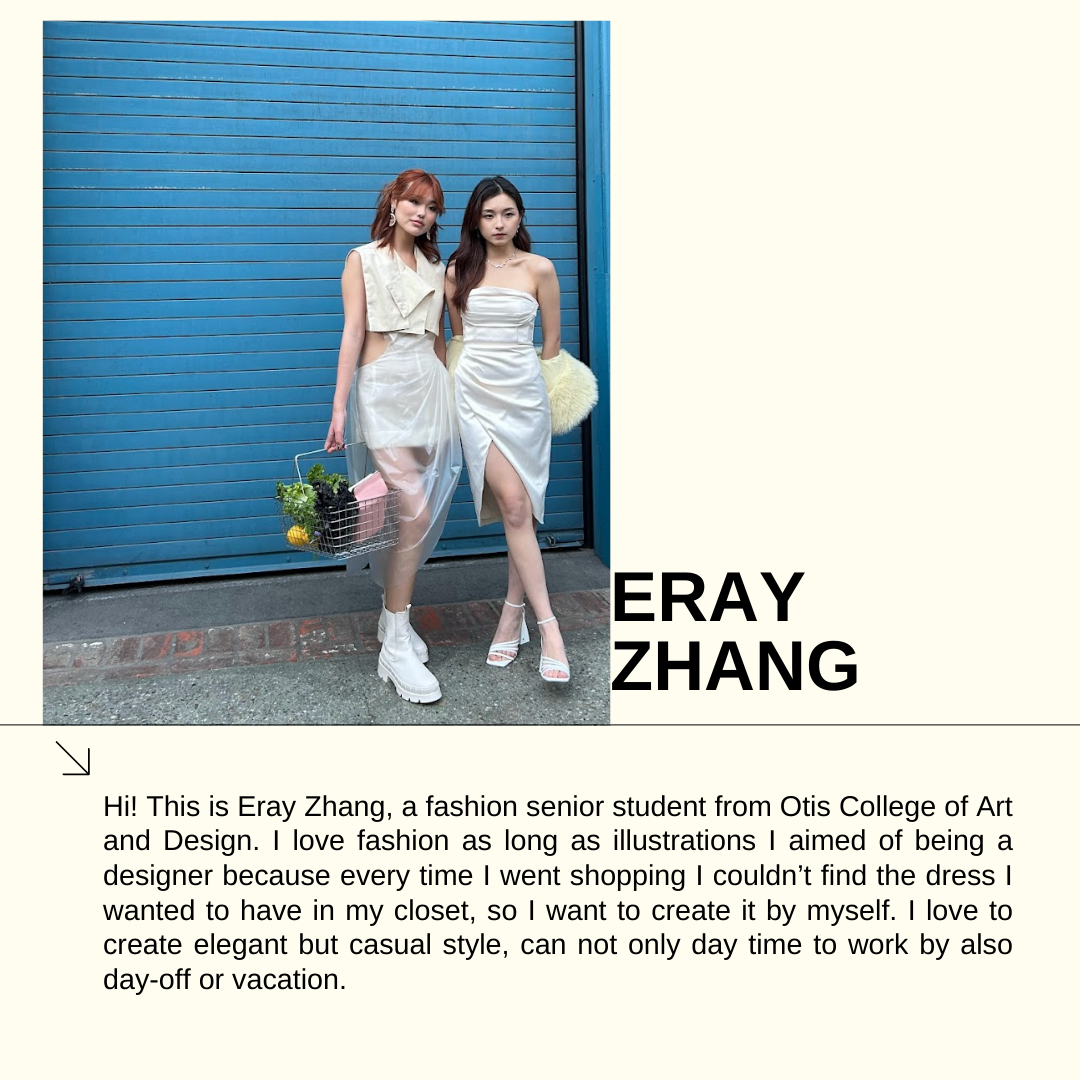

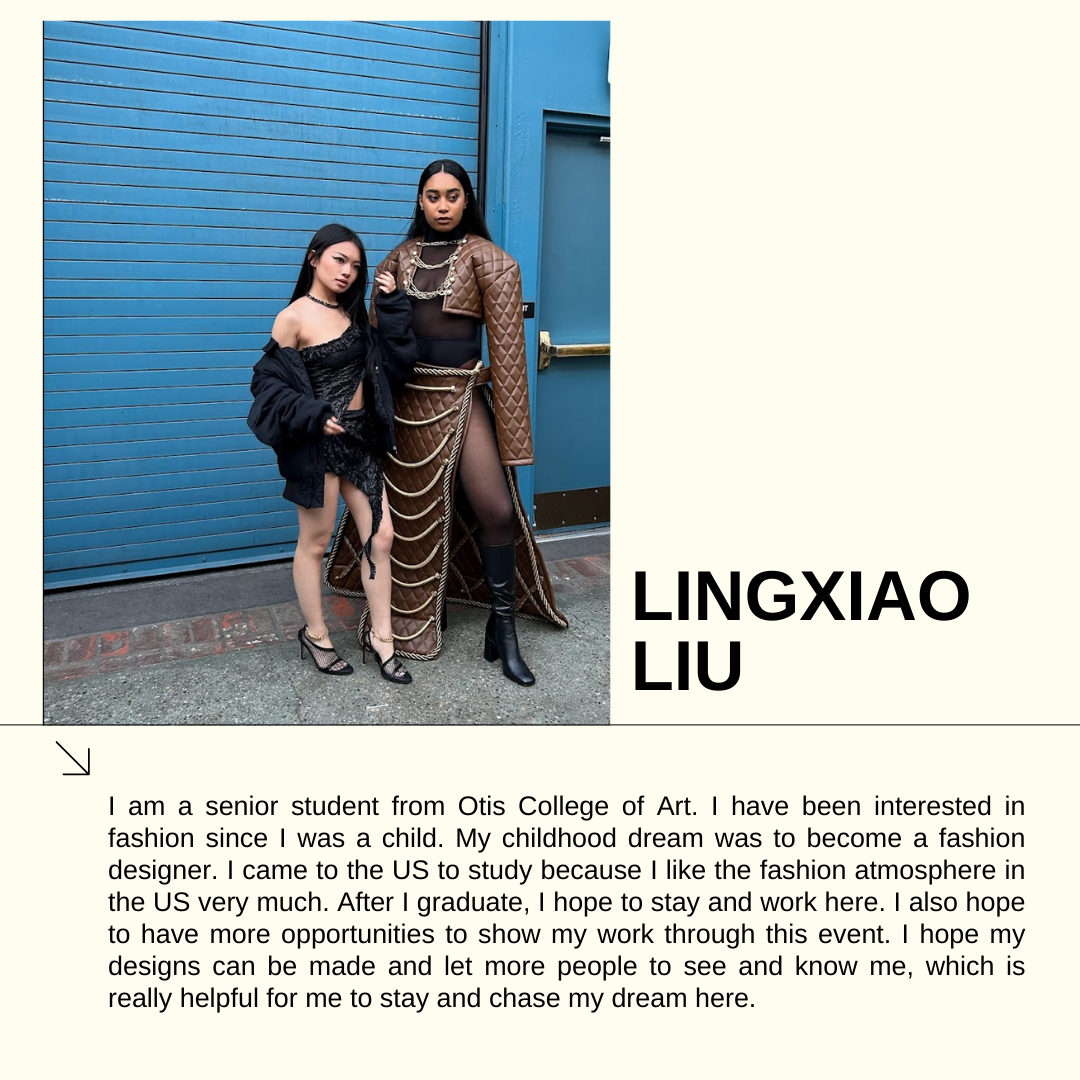

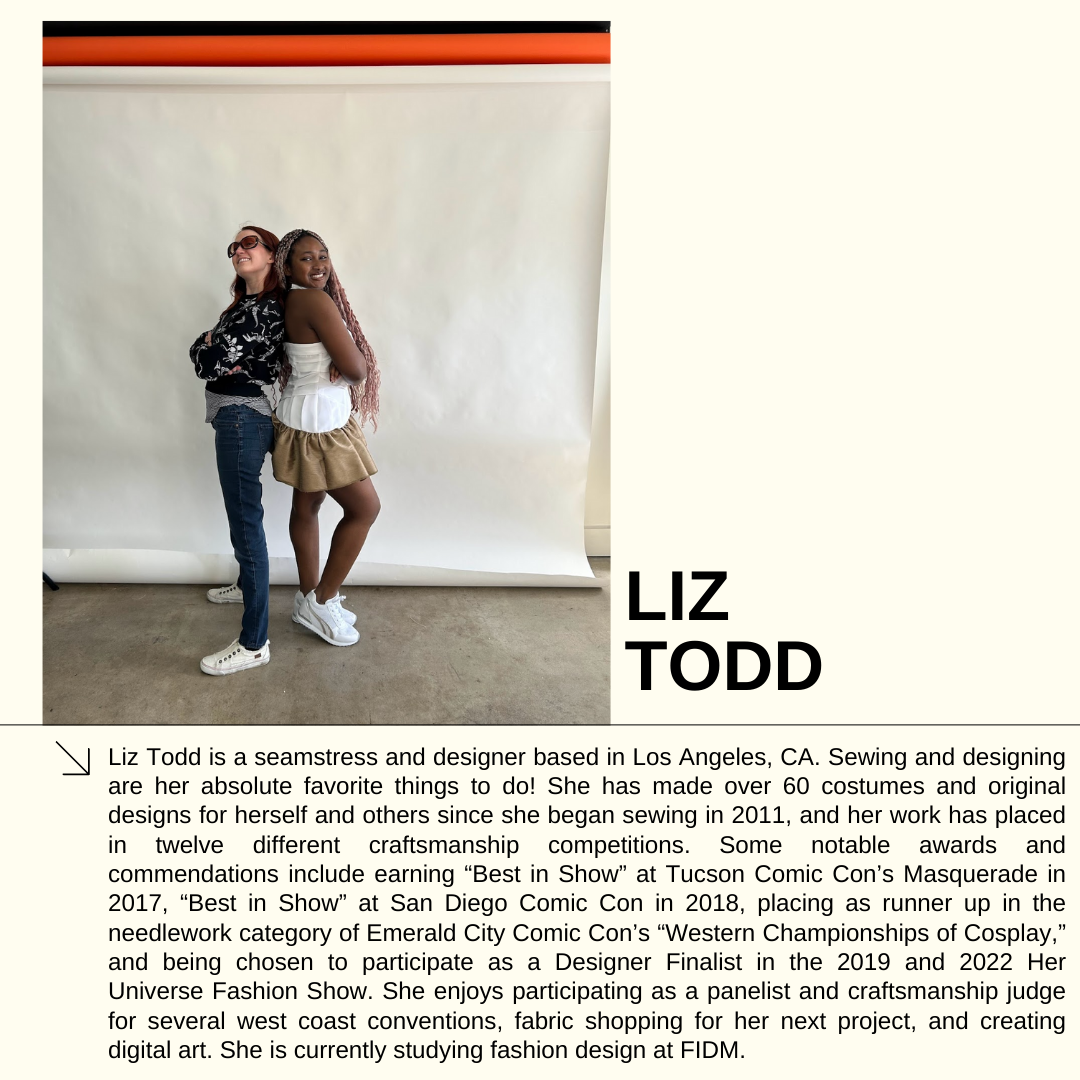

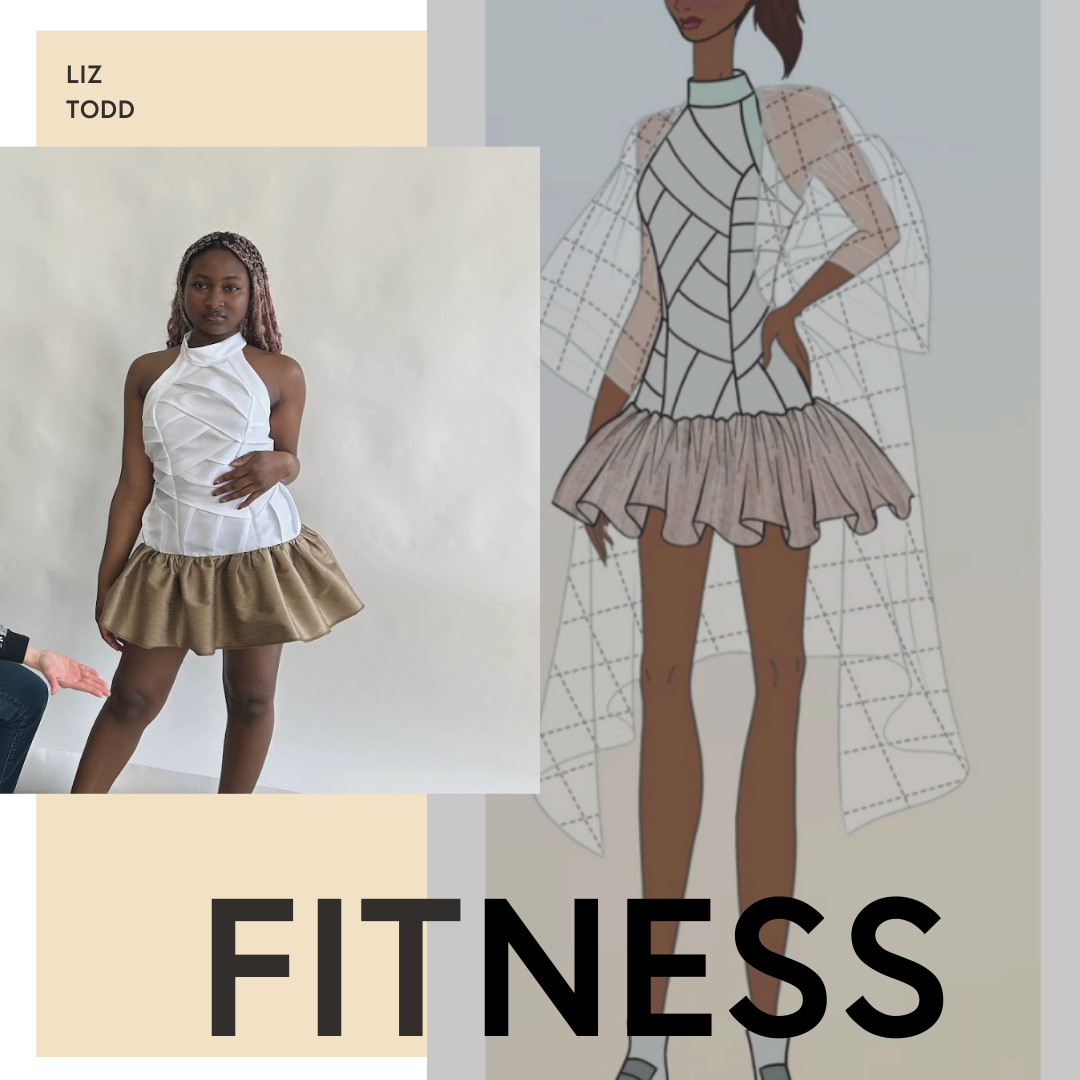

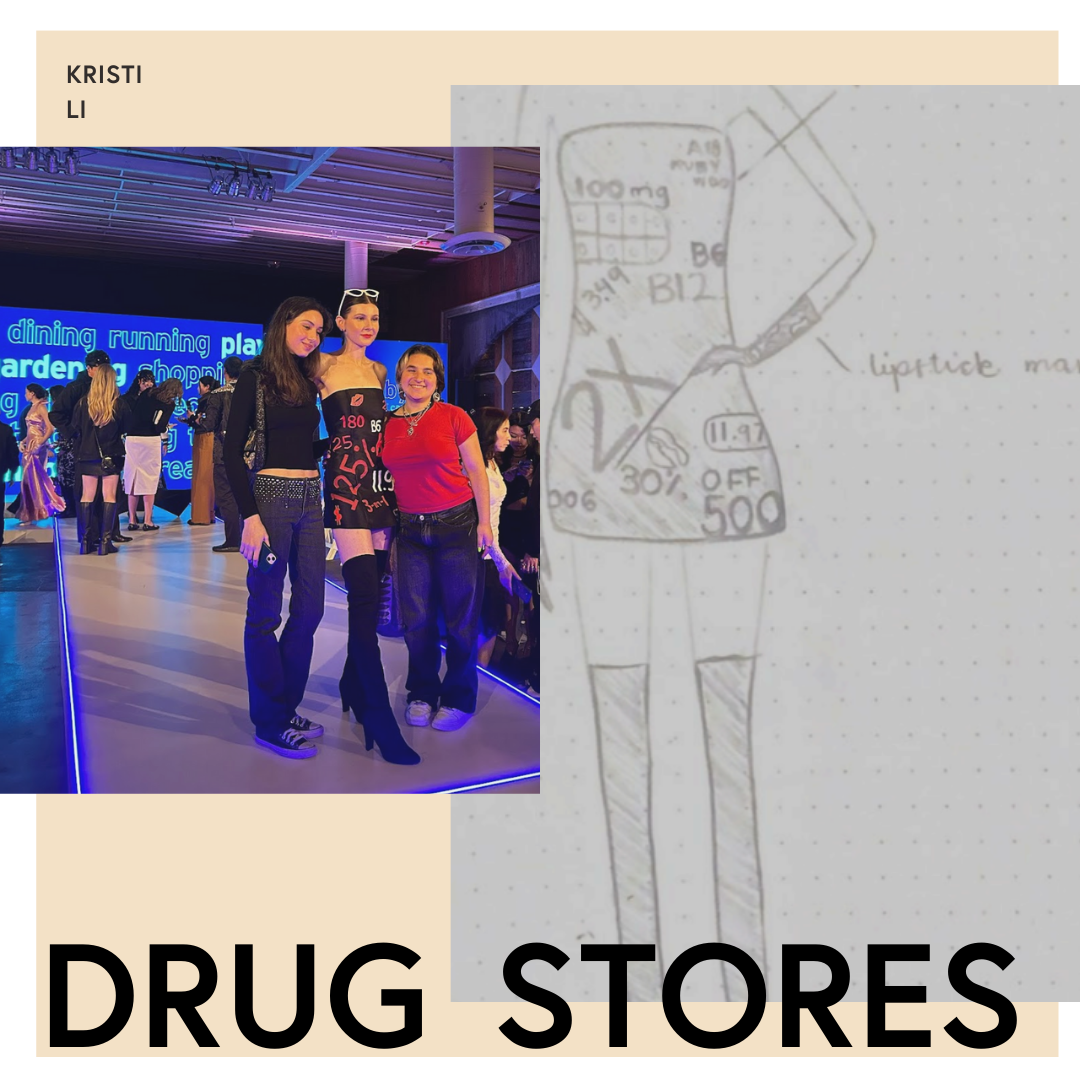

These values are richly entwined with the roots of the district and industry. Our team works with students, recent graduates, and designers who are new to the industry, all of who are eager to become a part of this industry and see their ideas come to life, together.

We have seen firsthand that there is a demand for the labor of this district. There is a need and want for this community of workers and businesses to not only exist, but flourish. The Garment District in Los Angeles represents almost the entirety of domestic US garment production at 83% of the nation's cut & sew apparel sales, creating $1.5 Billion in sales.

However, plans for redevelopment put our industry and district as it stands at risk.

“LA’s garment sector is at risk of displacement due to the The Downtown Los Angeles 2040 Community Plan. The plan, as drafted, will have a significant impact on the evolving Los Angeles garment industry and, most notably, the industry’s 45,000 skilled garment workers. It proposes a drastic shift of land use from largely manufacturing zones, to primarily ‘Markets’ and ‘Hybrid Industrial’ designations, both of which will significantly disrupt the balance of the irreplaceable Fashion District ecosystem. The detrimental consequences of the rezoning plan on the garment sector and its low wage workers cannot be understated.” - The Garment Worker Center

Across the country, we see this same disregard for labor and manufacturing result in the detriment of industry and production. The rezoning of New York City’s garment industry is a warning of what will happen to our own city if we do not unite against the 2040 rezoning plan. What remained of the NYC clothing manufacturing industry was halved between 2016 and 2020, and continues to collapse as it is rezoned and “developed.”

The Garment District is not a relic from a past industry, it is a living history of California Made production and generational labor. The district should not only be preserved, but nourished and enriched through thoughtful development.